fphf (Fixed-Point Hash Finder) is a tool I made that brute-forces the SHA-256 cryptographic algorithm to find strings that contain part of their own hash.

What does that even mean?

SHA-256

SHA-256 (Secure Hash Algorithm 256-bit) is a common cryptographic function that takes in a string of text and outputs a long string of gibberish characters called a hash. For example, here’s the hash of “Ethan is awesome”:

8a065cf798322fecf722768939f4ac3373a800ad7a34443d4bc22fba59fb1629

There’s no inherent meaning to those characters, they’re just pseudo-random gibberish. I said “pseudo-random” rather than “random” because if you re-generate the hash of “Ethan is awesome”, you’ll get that exact same string of gibberish. Every single time.

SHA-256 is extremely sensitive to even the tiniest changes. Here’s the hash for “ethan is awesome” (notice that the e is now lowercase):

06e30aaabafedce2249f3807f0ba1dc53e8ffef4a98753109c0313ddccc28ed3

Changing the capitalization of a single letter results in a completely different hash. This property is what makes SHA-256 useful. If you have a long string of text and you need to send it to someone, how can you be sure that it wasn’t tampered with en-route? You can transmit a SHA-256 hash along with the text, and the person you send it to can verify that the hash is the same. If it isn’t, that means that something (even just a single character) was altered in transit.

Fixed-point hashes

Fixed-point hashes are strings of text that contain part of their cryptographic hash.

Okay, technically a fixed-point hash is a string of text that equals its cryptographic hash, but it’s effectively impossible to find a true SHA-256 fixed-point hash. Using all of humanity’s combined computing power, it would take roughly 2.7x10^38 (270 billion billion billion billion) times the current age of the universe to brute-force a full SHA-256 hash. So because the term “fixed-point hash” isn’t being used for anything, I’m commandeering it for my own purposes. From now on, “fixed-point hash” refers to a string that embeds the first few digits of its cryptographic hash.

Anyways, it’s pretty difficult to find fixed-point hashes. If you try to make an arbitrary one, it’ll almost certainly be wrong. For example, the hash of the string “the SHA-256 hash of this string begins with 1234567” is:

8e3d0d011011364974bc31835f6b149549c5b5579e7218ca0e6619c023a7a699

The hash starts with “8e3d0d0” instead of “1234567”, so it’s not a fixed-point hash.

Let’s try using the first digits of the actual hash instead of our arbitrary numbers. The hash of “the SHA-256 hash of this string begins with 8e3d0d0” is:

ea1a5c1bfd87eba5ccd6746d7a29440bec4b399cba2e0174fa605ca7247bb262

Because we changed the string, the hash changed too. The hash starts with “ea1a5c1”, not “8e3d0d0”, so this isn’t a fixed-point hash either.

In many math explanation essays, the author will give examples like the ones that I’ve given as red herrings to make it seem like it’s an impossible task, then explain the clever mathematical trick that makes it possible. However, there isn’t a clever mathematical trick here. There is no known algorithm for reversing or manipulating SHA-256. SHA-256 is so secure that the United States military uses it to transmit top-secret files. There is no easy way to find fixed-point hashes.

Brute force

But just because there isn’t an easy way to find fixed-point hashes doesn’t mean there isn’t a way. If you just randomly guess-and-check hashes, you will (probably) eventually find one. Depending on how long of a hash you want, you’ll have to guess anywhere from a few hundred to many trillions of combinations.

With a seven-digit hash, the search space is 268 million possible hashes. I don’t really want to guess hundreds of millions of combinations manually (please forgive my laziness), so I wrote some code to make my computer do it for me.

Using fphf

fphf is a tool for quickly and easily finding fixed-point hashes. It uses the computational power of modern consumer CPUs to search a hash space for fixed-points.

In order to use it, you’ll need to install Git and install Rust (if you haven’t already), then run the following commands:

1git clone https://github.com/ethmarks/fphf.git

2cd fphf

3cargo install --path .

This will install fphf onto your computer. If you don’t want to install it, you can also substitute the cargo install --path . command for cargo run --release --, which will run it without installing it.

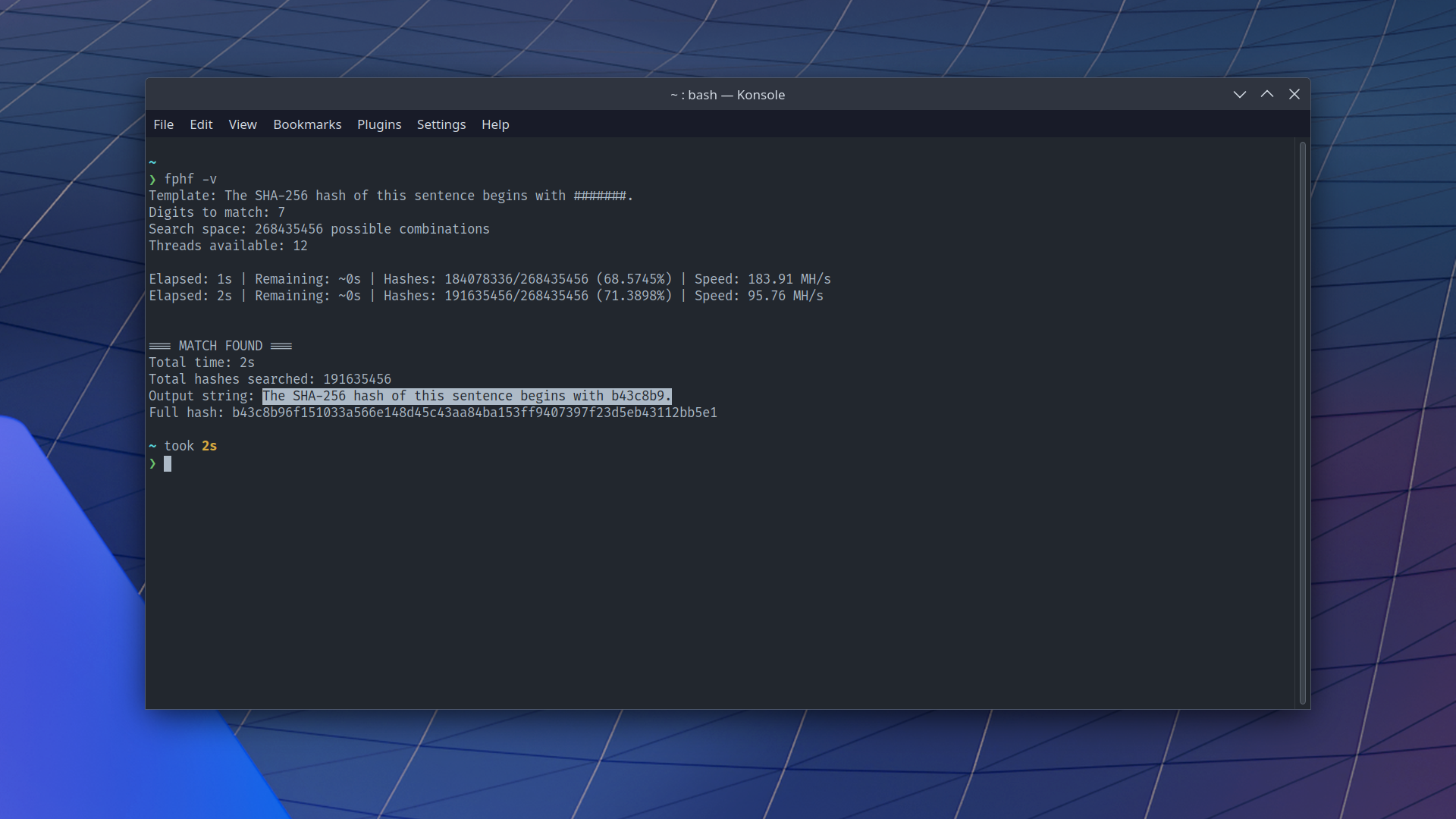

If you just run fphf on its own, it’ll use the default parameters, which are to find a 7-digit fixed-point hash for the string “The SHA-256 hash of this sentence begins with #.”, but you can also customize the options as described in the fphf options documentation

.

How long fphf takes to run depends on your hardware and the options you choose. fphf is written in Rust and uses rayon for multithreading to try to squeeze out as much performance as possible, but brute-forcing SHA-256 is fundamentally a computationally expensive task. On my 12-core laptop, running fphf with the default 7 digits only takes around 2 seconds. However, if you make it find a longer hash, it’ll take far longer. An 8-digit hash takes about 27 seconds for my computer to find and a 9-digit hash takes around 14 minutes. Put formally, the search difficulty grows exponentially with O(16^n) complexity. Put informally, don’t use fphf to find large hashes unless you’re willing to let your computer work on it for the foreseeable future.

Why?

Fixed-point hashes are cool. They aren’t useful, but they are cool.

It’s kind of like bare-handed apple splitting. Ripping apart an apple with brute force requires (by my calculations) exerting around 150 PSI of pressure on the apple. For context, the recommended pressure in a car tire is around 30-40 PSI and the maximum pressure is 51 PSI. Putting 150 PSI in a tire would cause the thick styrene-butadiene rubber to burst open. Nobody could put that much pressure on an apple using only their hands. So if you see someone rip an apple in half , it seems like a superhuman feat of strength. It’s not (there’s a technique involving structural weak points in the apple) but it seems really impressive unless you know that.

Likewise, because it’s unfathomably difficult to brute-force SHA-256, the existence of a known fixed-point hash (especially one with a custom message) implies that either you found a way to reverse SHA-256 or you used obscene amounts of computing power to find it. Either of those possibilities would be extremely impressive. Neither of them are true, but until someone figures that out, they’ll be very impressed. That’s the purpose of fphf: those few seconds of ‘oh my god, how did they do that?’.

The first time I saw a fixed-point hash , I was stunned. I thought that the author must have figured out some black magic bit-twiddling trick or spent thousands of dollars renting time from supercomputers. In reality, he just wrote a single-threaded Rust script to find fixed-point hashes and let it run for 12 minutes on his Mac.

My goal with fphf was to spread that feeling of temporary awe to as many people as possible by making it easy for people to create custom fixed-point hashes to flaunt.

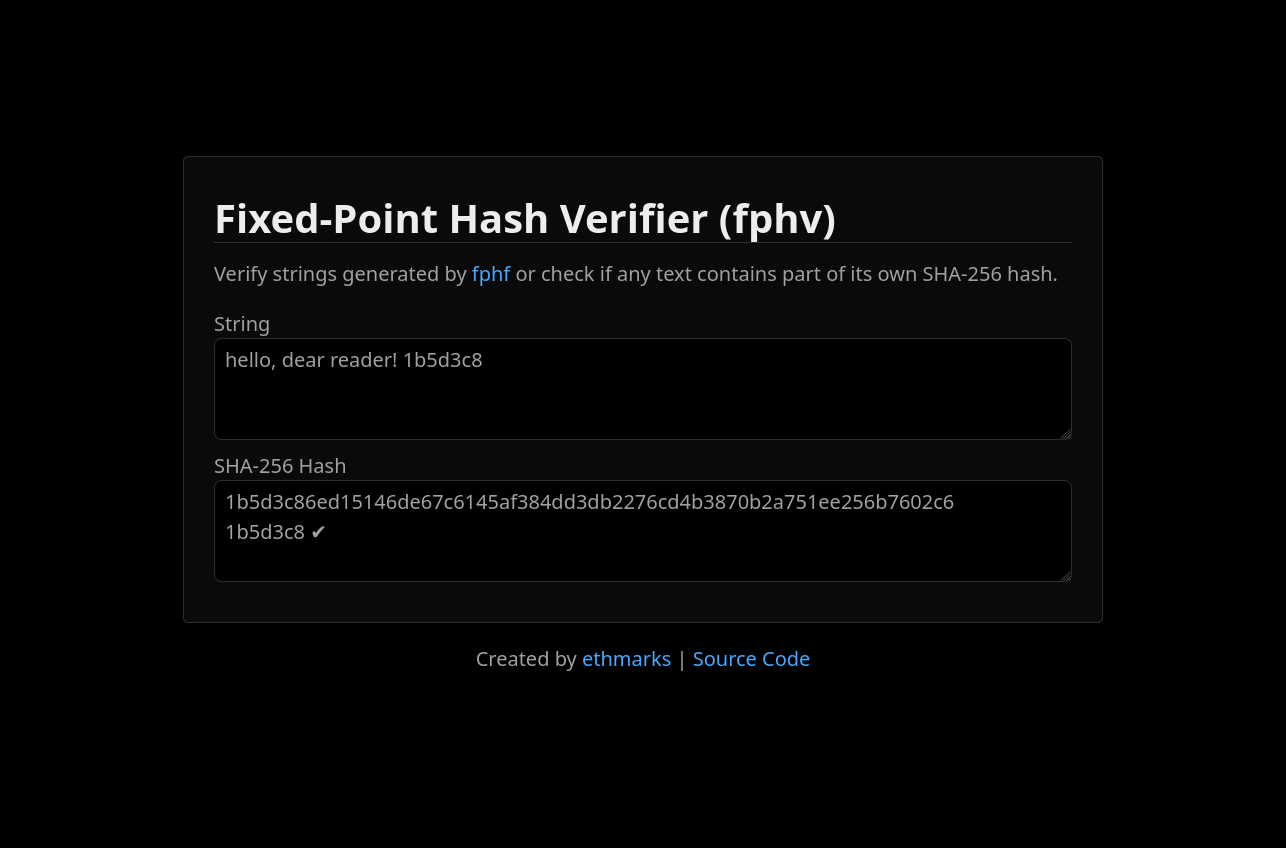

Fixed-Point Hash Verifier

I also made a companion project to fphf called fphv (Fixed-Point Hash Verifier). It’s a little web app made with Svelte that calculates SHA-256 hashes in your browser and uses a matching algorithm to check if the input string is a fixed-point hash.

To use it, simply visit https://fphv.vercel.app/ and copy-paste your string into the input textbox. fphv will calculate the SHA-256 hash and display it in the output. If it’s a valid fixed-point hash, fphv will display the section of the hash that matches the input string and add a little checkmark.

There are other ways to check SHA-256 hashes (e.g. the sha256sum utility on Linux), but to my knowledge none of them come with built-in fixed-point hash checking.

Conclusion

fphf is definitely not my most useful project, but it is probably my most fun project. I really like it and hope that you do too. Feel free to use it however you want. For example, you could include a fixed-point hash in your bio to make people briefly consider the possibility that you’re a genius cryptographer who cracked SHA-256. Anyways, the hash of this paragraph begins with 5afd152.

~Ethan