Note: This was written as a project for my English class. I didn’t intend to publish it, but after spending days iterating on it and also writing over 300 lines of code for the web demos, I decided that I spent too much effort on this not to publish it.

Introduction

Most maps these days use the Mercator Projection. It’s pretty much the default map projection. Google Maps uses it, for example.

But the Mercator Projection is not a recent invention. It’s been the de-facto standard for the last 400 years. It was invented by a cartographer named Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It became massively popular because it used clever mathematics that made it very useful to ships at sea. More on that later.

Anyways, the first map to use the Mercator Projection was made by Mercator himself. It’s called the 1569 Mercator World Map. It was basically a tech demo for the Mercator Projection: it was very exciting, but it had massive flaws that made it completely unsuitable for general use.

A note on terminology

I use a few different terms that include the word ‘Mercator’, so just to clear up any confusion, here’s a little cheat-sheet.

- “Mercator”: the guy who made the things I’m talking about

- “Mercator Projection”: the special way of drawing maps that Gerardus Mercator invented

- “the Mercator map / Mercator’s map”: the map made by Gerardus Mercator in 1569 that used the Mercator Projection

- “a Mercator map / Mercator maps”: any map that uses the Mercator Projection; this includes the Mercator map, but it also includes the map in your second grade classroom

The map

First, let’s see what the Mercator map actually looks like.

You could just use Google Images or whatever, but those images are going to be pretty low-quality. For a world map, we want a high resolution image so that we can zoom in.

The highest-resolution images of the 1569 Mercator World Map that are freely available were taken by a German secondary school teacher named Wilhelm Kruecken. He took 18 high-resolution photos, each of a different section of the original map. I composited these photos together into one 5,433 by 3,450 pixel image. I then upscaled the composition with a Nomos8k neural upscaler to create a 10,866 by 6,900 pixel image. This makes it one of the highest-resolution images of the original Mercator map available on the public web. It can be downloaded here .

I coded an interactive demo so you can explore the map. Zoom in to see all of the detail. The source code is available here .

Obviously, this map is very very wrong. It looks like something you might draw if you were really fastidious with Europe and Africa but then outsourced the rest of the map to a seven-year-old. At a glance, you might assume that this a map from a fantasy novel rather than a map of Earth.

But it gets so much worse.

Stuff he just made up

That’s not what the Americas are shaped like

The Americas are the most obviously wrong part here. Canada is enormous, the area that would eventually become the United States is squished, and South America is shaped kind of like a piece of toast.

The reason the Americas are so hilariously misshapen is that nobody knew what they looked like at this point. This map was created barely a century after Christopher Columbus landed, so the vast majority of the New World was still unexplored to Europeans. Surveying unknown land is difficult, and it’s even harder the land is a continent-sized rainforest with jaguars and venomous snakes. It’s understandable that they didn’t have a great idea of what South America looked like.

r/mapswithoutaustralia

Probably the second most obvious mistake is the absence of Australia.

There’s not really much to say about this one. Australia wasn’t known to Europeans until 1606, so Mercator didn’t know that Australia existed. Fair enough.

Even though this wasn’t strictly Mercator’s fault, ’leaving out an entire continent’ is pretty much the worst mistake one can make when creating a world map.

Antarctica looks fine at least… right?

You might be wondering ‘Since Antarctica was discovered after Australia, and this map predates the discovery of Australia, how come Mercator put Antarctica on this map?’. That’s a very astute question. The answer is: ’that isn’t Antarctica’.

The massive continent on the bottom of the map is called Terra Australis . You haven’t heard of it because it doesn’t exist.

Let me explain.

In the 1400s, cartographers noticed that Earth had lots of land in the Northern Hemisphere but not as much land in the Southern Hemisphere. Based on the unfounded assumption that Earth must be symmetrical, they concluded that there must be a massive continent somewhere in the Southern Hemisphere.

Even though nobody had ever surveyed this continent, seen it, heard about it, or acquired any empirical data whatsoever to suggest that it exists, cartographers decided that it totally definitely existed. They named it Terra Australis, Latin for “Southern Land”.

They sketched a coastline based on what it looked like in their imaginations, then told everyone that there was a lush, forested mega-continent below South America.

I take it back. Leaving out a continent isn’t the worst map-making mistake; including a made-up continent is even worse.

Ah yes, the island of “Frisland”

Not satisfied with including a made-up continent, Mercator also included several imaginary islands in the Atlantic Ocean.

These are examples of phantom islands . Phantom islands were a pretty common occurrence. When “Bob said he saw an island” was sufficient evidence for putting that island on every map, there were quite a few times where sailors claimed to have seen islands that don’t actually exist.

What is “North”, anyways?

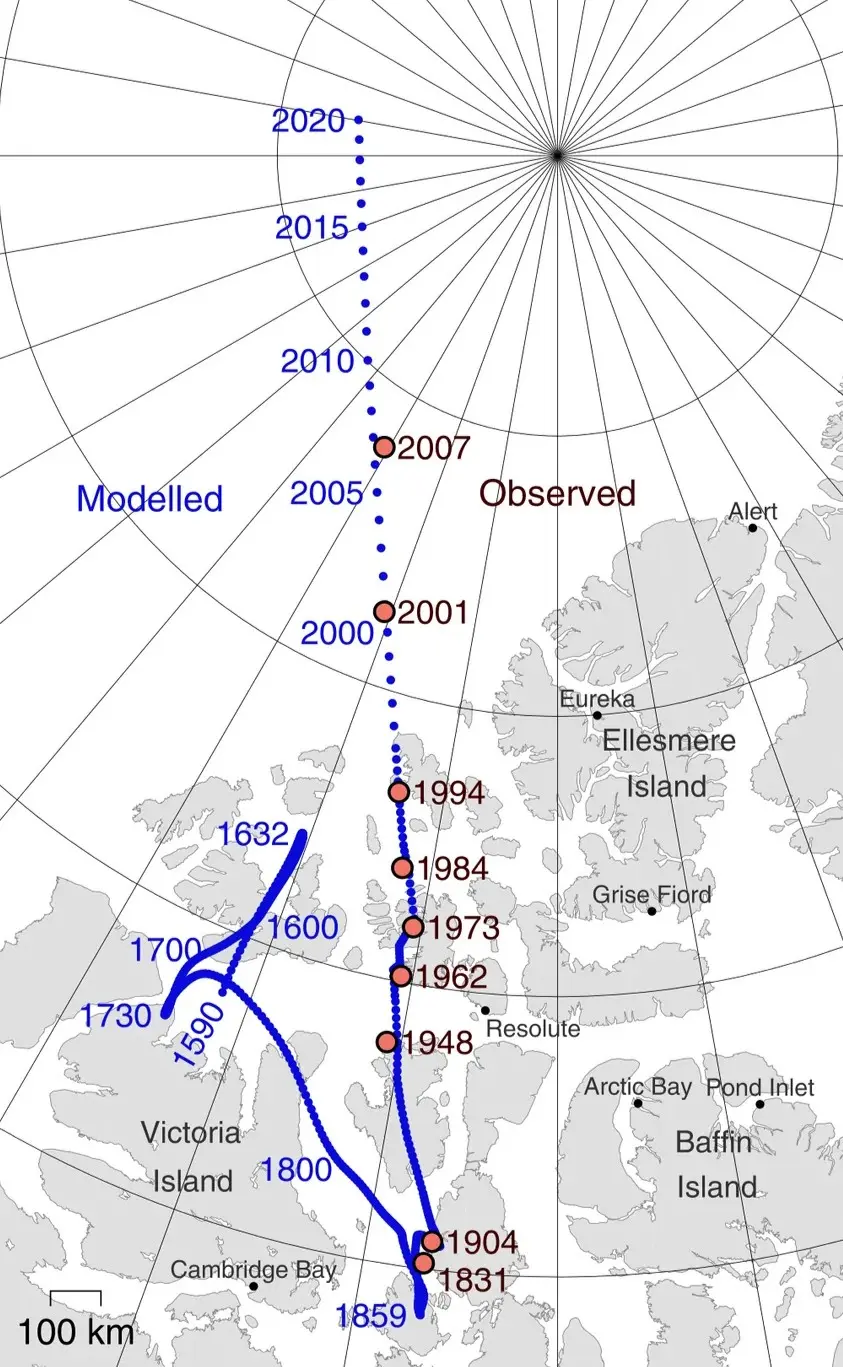

There are lots of different ways to define North. There’s Magnetic North, Geographic North, Grid North, Geomagnetic North, Astronomic North, and a bunch more, but the two big ones are Magnetic North and Geographic North.

Magnetic North is the North that a compass points to. It’s basically just the average polarity of the iron atoms in Earth’s mantle. Because Earth’s mantle is a constantly-shifting sea of molten metal, the average polarity can change pretty quickly, even on a human timescale. This causes Magnetic North to move. In 2025, Magnetic North is pretty close to Geographic North, but in 1569 it was in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago, hundreds of miles away from its current location.

In the modern day, it’s trivial to figure out exactly which direction Geographic North is by using your phone, but that’s only because your phone can interface with GPS and has built-in accelerometers and gyroscopes. When all you had was a compass, the only North that you knew how to find was Magnetic North. This means that most actually useful navigation maps set the ‘up’ direction as Magnetic North. Instead, Mercator’s map was oriented to Geographic North. This alone made it basically useless for sailors of the time.

Where exactly did he get this data?

Mercator didn’t personally survey the globe, nor did he commission other people to do it for him. His map was based entirely on preexisting charts. All he did was aggregate them and convert them to his new projection.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with using preexisting charts. Most cartographers in those days copied the work of their peers.

The problem with Mercator’s approach was that he failed to use the charts properly.

Mercator assumed that all of the charts he was aggregating used the exact same square grid. They didn’t. Some of them used the square grid he thought they did, while some used entirely different grids. Mercator didn’t notice this, so he used the same algorithm on all of them. This led to lots of dissonance between the different charts.

To understand how much of a problem this was, imagine that you had a few dozen old-timey silver halide photographs of the same scene taken at different angles. Some of the photographs are properly exposed, some are underexposed, and some are overexposed. You develop them all using the exact same chemicals for the exact same amount of time, then cut pieces out of them and re-assemble them to form one big image. The final result is going to look like a jumbled incoherent mess because many of the photos weren’t properly processed and they were just crudely amalgamated together.

This is the biggest problem with Mercator’s map. The charts he used weren’t accurate in the first place (remember the imaginary continent that they insisted was real?), but Mercator made their errors even worse by failing to properly handle them.

What about the Mercator Projection?

Hopefully I’ve now convinced you that Mercator was bad at making maps. His world map was pretty bad for its time, but it’s even worse when compared to modern satellite imagery.

However, the Mercator Projection that his map used was genuinely revolutionary. This is because it was the first map in the world to make all rhumb lines appear straight. This is something that nobody else in the world was able to do before Mercator.

Why are straight rhumb lines so important?

In order to understand why the Mercator Projection was such a big deal, you need to understand why straight rhumb lines were such a big deal. In order to do that, you need to understand what rhumb lines are in the first place.

Essentially, rhumb lines, also called constant bearings, are just straight lines relative to a direction on a compass. If you follow a specific compass direction (e.g. 30 degrees north of west) in a straight line, you’re traveling along a rhumb line. On anything other than a Mercator projection (including, you know, the actual Earth), rhumb lines aren’t straight. They’re curves that spiral towards either the North or South pole.

But the Mercator projection is designed so that all rhumb lines appear straight. This is what makes the Mercator projection special.

The way to construct a map with straight rhumb lines using modern mathematics is to set the apparent latitude as the integral of the inverse of the cosine of the true latitude. In other words, calculus stuff. Calculus hadn’t been invented yet, so Mercator must have done something else. Unfortunately, we’ll never know for sure exactly how he did it because Mercator was extremely secretive about his method. Nobody else even knew how the Mercator Projection worked until Edward Wright reverse-engineered it 30 years later.

Anyways, straight rhumb lines are useful because they make navigation by compass way easier. With a Mercator map, navigation is as easy as drawing a straight line between your current position and your destination, measuring the angle of this line relative to North, and sailing in the direction your compass points when set to the angle you measured. And that’s it! This was much more simple than the complicated geometry that navigators used to have to do in order to plot a course.

Rhumb line courses aren’t the shortest path between two points on a globe. Planes and modern ships almost exclusively use great circle routes because they’re faster and more fuel-efficient, even if they’re more difficult to plot.

But for a ship at sea, being able to plot a course in a few minutes and being able to keep that course by just following a certain direction on your compass was invaluable. Fewer steps in the plotting process means less room for error, and error in your plot means starving to death on the open ocean: not ideal.

This is why the Mercator Projection was so popular. To 16th-century sailors, it was literally life-saving.

The Greenland Problem

That being said, the Mercator Projection has its share of flaws.

The most well-known downside of the Mercator Projection is the “Greenland Problem”. If you look at Greenland on a Mercator map, you’d get the impression that it’s about the same size as Africa. Maybe a bit bigger.

In reality, Greenland is 14 times smaller than Africa. This is because the Mercator Projection makes things bigger based on how far they are from the equator. Africa is pretty close to the equator, so it’s more or less normally sized. Greenland is pretty far from the equator, so it looks absolutely enormous.

Here’s another demo I coded. Drag Greenland around. See how much smaller it gets when you bring it close to the equator? The source code for this one is here .

The North Pole isn’t infinitely large

The Mercator Projection also can’t show the North or South poles. I said “things get bigger when they’re further from the equator”, but a more technically precise way to describe it is ’things get bigger when they’re closer to the poles’. This might not sound like a big difference, but it is. The consequence of doing this is that the North and South poles would have to be infinitely large (a distance of zero means size approaches infinity), and the area immediately around them would be hundreds to thousands of times larger than the rest of the map.

This obviously isn’t practical or possible to show, so most maps using the Mercator Projection just omit 5-10 degrees of latitude from the top and bottom of the map. This means that about 1/25 of the Earth’s surface are isn’t even shown at all on Mercator maps.

This is a pretty big disadvantage for something like polar exploration or international flights that pass over one of the poles.

It’s not even a good tech demo

The problem with Mercator’s map is that the Mercator Projection’s cleverness relies on the map being accurate in the first place. As you’re aware, ‘accurate’ is not a very good descriptor of Mercator’s map.

It doesn’t matter that you can draw a straight rhumb line between, say, England and Bermuda if the map is wrong about where Bermuda was by hundreds of miles.

Mercator’s projection was genuinely revolutionary (at least, for a few hundred years until we started using great circle routes), but his map was too riddled with errors to properly showcase it.

Conclusion

Gerardus Mercator is kind of a paradox.

On the one hand, he was a brilliant mathematician who designed a map projection that revolutionized navigation and would be used for centuries to come.

But on the other hand, he was a terrible mapmaker who left out a continent, made up a new one, used the wrong type of North, and failed to properly use the charts he based his map off of.

Though the Mercator Projection revolutionized navigation, it didn’t do so until 1599, 30 years after it was published and 5 years after Mercator died, when Edward Wright published the Wright–Molyneux Map . This map also used the Mercator Projection, but its data was much more accurate. This is the map that navigators used, not Mercator’s map.

Given the choice between using Mercator’s map and manually plotting route geometry across the Atlantic Ocean, they chose the latter. This is because it was a bad map.

Mercator was a visionary mathematician who sucked at implementing his ideas in practice.

His map was not useful for navigation.

~Ethan